Cooder imagines, in stories and songs, a homeless tabby, Buddy Red Cat embarking on a Bound for Glory–like journey across country. Singer-songwriter Billy Bragg considers it a favorite and tells the New York Times: “Woody Guthrie's spirit runs through this record very strongly.” London’s Observer describes it as “a light-hearted, sometimes poignant elegy for the American working man and his music.”

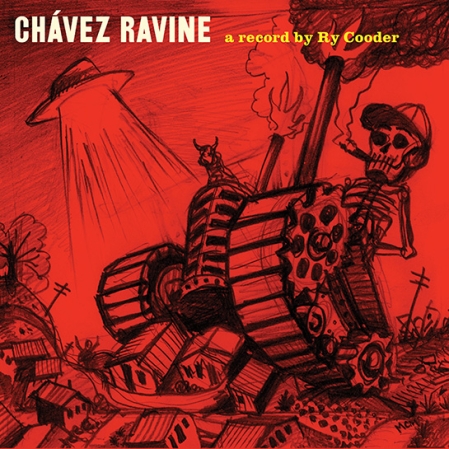

In 2005, as Ry Cooder was knee-deep in some ninth-inning tinkering, finishing up his forthcoming album, Chavez Ravine, a peculiar message sailed in—one could say—from deep out-of-left-field. It arrived by way of US Mail, slipped into a nondescript, manila envelope, addressed in an old friend’s recognizable scrawl. Inside, he found a familiar image of the great bluesman, Leadbelly. Yet, photo-shopped in place of his face was that of a red cat; an inscrutable, seen-it-all expression hovering in his eyes. He found little else, except a web address and this note: “You’ll know what to do with this.”

But not right away. After some initial poking around to learn this red cat’s name (“Buddy”) and a bit of his vagabond story (he was found in the alley behind a record store in Vancouver, living in a suitcase, and he’d passed away in 2005), he pushed it aside to tie up pressing loose ends. But the notion had already crawled up inside somewhere deep in his imagination.

“Over time something was coming to me,” he says. Propulsive rhythms and hardscrabble stories and scraps of ocher-toned melodies began to spin round inside. “I kept thinking ‘red cat,' and I kept hearing an old Charlie Poole song—a cadence.” It began to slide together. “He’s a red cat—not just red colored, but he’s a union man. He becomes Red.” Next, a piece of lyric. "I’m a red cat till I die.” Soon enough, the itinerant Buddy had a back-story; some fellow travelers he meets along the road—Lefty the Mouse, the Reverend Tom Toad—a past and a future; a story to tell.

My Name Is Buddy: Another Record by Ry Cooder is, in a certain respect, Ry Cooder circling back, revisiting a body of music that has for much of his life held a certain fascination. “When I first started doing records. I thought, ‘I like these old songs. These dustbowl songs.’ So I made a couple of records and people thought: ‘What’s this?’ You can’t sell this.’ But I kept making these things, again and again, because I knew a good song,” he says. “I’d say it’s taken me 40 years to get it right.”

If Chavez Ravine was Ry Cooder’s musical palimpsest, his re-imagining of a lost neighborhood, a lost way of life, My Name Is Buddy is the next chapter revisiting those themes of displacement, disenfranchisement, deteriorating democracy—but through the story of a band of friends, in the tradition of Walt Kelly’s Pogo: “Pogo to me was a roadmap to life. Animals are perfect characters because they don’t say much. They’re beautiful metaphors. Very solid, not so hard to understand.”

Part allegory, part picaresque adventure, the album takes up where Chavez Ravine left off. It continues Cooder’s examination of a disappearing America, in this case the vanishing American “working man”. “Nowadays nobody wants to be called a ‘working man’—an SUV driver maybe, but not a working man.” But what happened to this message of unity? Of solidarity? Of fairness or justice? What happened to the notion, “We are many, they are few.”? These questions put Cooder on a path revisiting the place where so many of those old stories and struggles have been stowed away for safe-keeping; the country’s foundation of music—its songs of praise, of sorrow, of work, of protest, of celebration. “What do poor people sing about? Death, Jesus, Mother and what happened today. They lived in poverty or worked in the mill and got their fingers chopped off —something horrible like that—but they carried that music along with them.”

Buddy’s suitcase, says Cooder, is “like his trailer, his Airstream, you could say,” but his travels aren’t just geographical. While the album weaves through a history of American, regional music—blues, folk, bluegrass with flavors of storefront spirituals and lounge jazz folded in—it also takes a turn through America’s philosophical soul: songs of strivers, of union men, church folk, and those down-at-the-heel heroes. If the music feels familiar, their melodies recognizable, they should, says Cooder. Many of them have hovered in our collective backspace for decades. “Most of these songs are based on other tunes, some of them hymns.” Shot through as well are nods or allusions to Reverend Gary Davis, Earl Robinson, Harland Howard, Hank Williams, Woody Guthrie, the protest songs of labor organizer and songwriter, Joe Hill.

Like Chavez Ravine, telling a specific story freed him: “I had to forget about Ry Cooder and tell this story.” (The scope’s span surprised him. What didn’t fit within the space of a song, became an accompanying book—the text written by Cooder, the illustrations cleverly imagined and deftly drawn by artist Vincent Valdez—that provides context. “The songs are a little more light-hearted,” says Cooder, “and the stories, a little darker, fill in the background.”)

To tell it properly, musically, Cooder went to key source folk, tenders of the True Vine of American hearth music: He traveled to Beacon, New York, and sat in with Mike and Pete Seeger for a historic session (“J. Edgar”) in Pete’s living room, featuring the two brothers on twin banjos. He rounded up bluegrass mandolin maestro Roland White and Chieftains leader Paddy Maloney. He called on old friends and frequent musical companions Jim Keltner, Van Dyke Parks, Flaco Jimenez, Mike Elizondo, and his son, Joachim Cooder. And though there are standout cameos by jazz musicians Jacky Terrasson and Stefon Harris (“Green Dog”), it’s not a cross-genre / cross-generation jam-session.

“I’ve always been interested in American vernacular music. How people sat in separate towns and wrote songs and played their instruments. I’ve always been interested in how they arrived at the songs, how they got into them, who taught them how to play their guitar, their fiddle. How they learned to hold it. And how it changed, from town to town, every 20 miles or so, like language, And how, before recordings, it all spread throughout America.”

Though My Name Is Buddy feels authentic, like some lost artifact plucked out of time, it is full of urgent resonance. “We’re not doing this to be nostalgic,” Cooder stresses, especially when so many of the same issues plague and flummox us today: bigotry, poverty, violence, greed, fair-access.

“I loved these songs; I love the melodies and the messages," says Cooder. "These songs are a template.” The idea is to craft them into something your own. “Many of these songs had a warning to the ‘working man’ folded in, especially those 19th-century songs in three-quarter time. It was the very reason for singing. Those songs were about topical things. They were vehicles for people who had a point to get across. Otherwise, there is no point in doing it.”

—Lynell George, December 2006

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Produced by Ry Cooder

Recorded by Don Smith at Sound City

Studios, Van Nuys, California

Additional recording by Sunny D. Levine at Orange Stella Studio, Santa Monica, California, and in Beacon, New York; Martin Pradler at Chateau Martín, Los Angeles

Mixdown by Don Smith and Martin Pradler at Sound City Studios

Mastering by Martin Pradler

Production Assistant: Aisha Ayers

All songs written by Ry Cooder, except tracks 5, 17, Traditional with new lyrics by Ry Cooder; tracks 6, 12 by Ry Cooder and Joachim Cooder; track 4 by Ry Cooder, Joachim Cooder, and Jared Smith

Illustrations by Vincent Valdez

Photographs by Susan Titelman

Package Design: Martin Pradler and Ry Cooder

79961

MUSICIANS

Ry Cooder, vocal (1-5, 7-10, 12-17), guitar (1-4, 6- 8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17), bajo sexton (5, 9), bass (6, 12, 13), mandola (13), keyboard (13), banjo (15)

Roland White, vocal (1, 5, 8), mandolin (5, 8, 9, 15, 16)

Joachim Cooder, drums (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 13), keyboard (14), percussion (14, 15)

Paddy Moloney, whistle (1, 17), uilleann pipes (1)

Mike Seeger, banjo (1, 4, 5), fiddle (1, 3, 9, 15- 17), harmonica (3, 8), jaw harp (3)

Van Dyke Parks, piano (2, 5, 9, 7)

Pete Seeger, banjo (4)

René Camacho, bass (5, 9)

Flaco Jiménez, accordion (5, 9, 17)

Terry Evans, vocal (6)

Bobby King, vocal (6)

Jim Keltner, drums (6, 12, 15-17)

Juliette Commagere, vocal (7)

Stefan Harris, vibes (7), marimba (7)

Jacky Terrasson, piano (7)

Mike Elizondo, bass (10, 15-17)

The original Cardboard Avenue Jaywalkers:

Buddy Red Cat, vocal (11), guitar (11)

Lefty Mouse, fiddle (11)

The Reverend Tom Toad, tambourine (11)

Jon Hassell, trumpet (14)

Juliette Commagere, vocal (16)