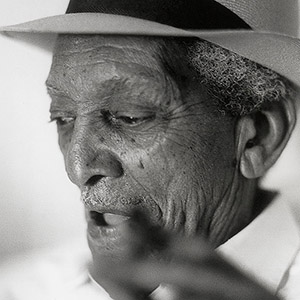

This is the music of a man who represented a century in his own right. There he is, with his neat narrow-brimmed hat, wide, generous smile, a Havana cigar ever burning between his fingers and a glass of mature rum in his hand to soothe the throat. And his armónico is always there, at the ready—a kind of guitar he invented to look like a guitar but to sound like a tres, the string instrument that takes the lead in all traditional Cuban music.

This man of the century was born Francisco Repilado in 1907, and over the years became known forever as Compay Segundo. In Cuba, when a man becomes the godfather of a friend's son, the two are called compadres. Compay was born in Siboney, in the Oriente in Cuba, a region where language has its own particular distinguishing features; words are shortened and intensified. Instead of compadre, people say compay. But it's more than simple linguistic formula: the word symbolizes friendship, loyalty, commitment, a whole way of life lived out by Compay Segundo in everyday actions and in his music.

This musical man was always surrounded by sound. Although the members of his family were country folk who neither sang nor played an instrument, Compay grew up with the sound of nature and very soon became a fan of trova or ballads. The trovadores of his childhood were strong, sturdy men with a gypsy air about them. From an early age, Compay was fascinated by one of the trova legends, Sindo Garay, a skinny performer with squinting eyes and a poet's soul, whose complex and beautiful tunes were an integral part of Cuba's national identity.

In his teens, Compay discovered the city of his dreams: Santiago de Cuba, on the shores of the Caribbean—a city stamped with the mark of the great cultural diversity of the region. With music overflowing inside him, he learned to read music and met Enrique Bueno, a wonderful woodwind teacher, who shared with him the secrets of the clarinet, and which was enough to earn him a place in the city's Banda Municipal and, later in Havana, in the fire brigade's official band. But his real talents lay with the guitar and singing, bochinches and seranatas. In Santiago, he would spend the evenings learning about music with Sindo and Ñico Saquito, himself a picaresque songwriter, and he got to know another mythical musician, Miguel Matamoros, who was to have a definitive influence on Compay’s musical career.

With son taking hold of the cities, sextets and septets became fashionable. In 1920s Cuba, with son already recognized as the richest, most stable form of musical expression on the island, the septet was born. Sextets and septets were popular because son was for dancing; people were crying out for them at social and family celebrations. Compay made his musical debut in a sextet called Los Seis Ases.

To earn a living, the young Compay learned the art of the barber and cigar making. And to satisfy his musical leanings, he wrote cancion, bolero, and guaracha and joined a number of different bands, among them Cuarteto Cubanacean, with whom he made his radio debut, and Quinteto Cuban Stars, with whom he traveled to Havana for the first time.

As a man of the world, Compay decided to settle down in Havana and set up Trio Cuba with two friends, Joaquín García and Evelio Machín. The trio played outside the offices of RCA Victor, where in the 1930s he later recorded his first album.

But it wasn't until the 1940s that Compay's talent was awarded with some serious luck. Trio Matamoros once again appeared in his life and invited him to play the clarinet in his legendary band. Compay teamed up with Lorenzo Hierrezuelo to form a duo that was to make history: Los Compadres. And it was then that Repilado started to call himself Compay Segundo; with Lorenzo taking the lead vocals and Compay, with his perfect deep tones, the second.

The recordings made at that time by Compay and Hierrezuelo are now an essential part of the collection of every lover of traditional Cuban music.

In the 1950s, Compay decided to make a go of it alone, and he formed the group Compay Segundo y sus Muchachos. Such was their success that when they traveled to the Dominican Republic in 1956, the fans of trova and son were begging them to settle down there.

At that time, Compay was combining his musical career with his job at H. Upmann, one of the most prestigious cigar manufacturers. He would get together with trova players such as Pablo Milanés and Sara González to play at bohemian musical gatherings; he was living out his mature years to the full. One day, after many years of employment at the factory, he decided to say goodbye to his day job and dedicate his time once more to music.

From that day, Compay became known worldwide as a musician and singer. Highlights in his career include being presented with the Cuarteto Patria at the Festival de Culturas Tradicionales Americanas, organized by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington (1989), the Primer Encuentro del Son y el Flamenco in Seville in 1993, and the concerts he gave with his band at the Café de la Danse in Paris in 1995.

Everything that followed is now part of the history books. Compay's fame spread throughout the world, performing one evening at the Paris Olympia, the next at New York's Carnegie Hall, then to London and Madrid, and on to Beirut and Buenos Aires. He won awards and more awards: a Grammy in 1998 for his participation in the first Buena Vista Social Club album; the Amigo prize given by Asociación Fonográfica y Videográfica Española; the Ondas, also from Spain; and an award from the Música de la Sociedad General de Autores y Editores. And more and more honors, like the Paris Ville medal, the Orden Félix Varela (the highest Cuban cultural recognition), and was named distinguished citizen of many South American and European cities. And throughout it all, he worked with the energy of a 20-year-old. Every record was a worldwide success: Yo Vengo Aquí, Antología, Lo Mejor de la Vida, Calle Salud, and Las Flores de La Vida became essential albums for every lover of traditional Cuban music.

Compay's team was like a family, beyond the two who were his flesh and blood sons, Salvador the double bassist and Basilio on percussion. On albums like his final Nonesuch release, Las Flores de la Vida, with Hugo Garzón on lead vocals, Compay's voice was the perfect, powerful complement; Benito Suárez provided a wonderful accompanying guitar; and Rafael Fournier added the bongos. Then, perhaps harking back to his days as a clarinet player, Compay added three magnificent clarinetists: Rafael Inciarte, Haskell Armenteros, and Rosendo Nardo—all from rigorous classical backgrounds.

Compay defied time itself with his rich vocal style. He loved, smiled, danced, made friends, and gave his heart. Is there any more to happiness?

—Pedro de la Hoz