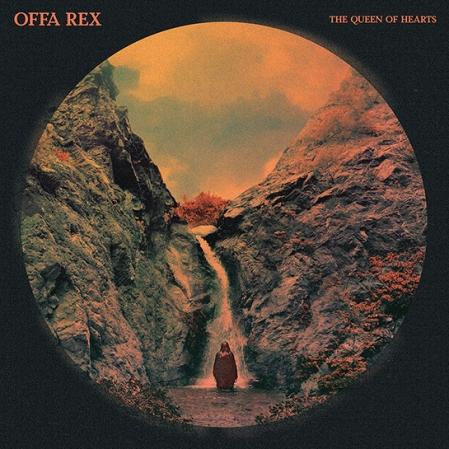

The Queen of Hearts is the debut album from Offa Rex, an adventurous project featuring Olivia Chaney and The Decemberists. The album draws largely on traditional English-Irish-Scottish repertoire to create a transatlantic musical conversation that flirts with psychedelia and folk rock while maintaining its own inimitable identity. NPR calls it "a match made in folk-rock heaven."

The Queen of Hearts, a collaborative exploration of traditional folk music from the British Isles by Offa Rex—English singer-songwriter Olivia Chaney and Portland, Oregon's The Decemberists—is clear proof of a wish granted. The Decemberists' Meloy had declared in a fan's note via Twitter that he'd give anything to hear Chaney perform "Willie O' Winsbury," an eighteenth century Scottish ballad that tells the dramatic tale of a sympathetic king who generously spares the life of his daughter's lover. It was preserved for posterity through the research of nineteenth century scholar James Francis Child and popularized in the late sixties by the Irish group Sweeney's Men and later by such British artists as Anne Briggs, John Renbourn, and Pentangle—among the musical antecedents to, and inspiration for, Chaney herself.

Hers is a voice uniquely suited to the British folk music Meloy loves, seventeenth to nineteenth century songs that were given new life, often with a psychedelic twist, by UK artists during the late fifties folk revival and then again during the late sixties and early seventies. Like many others, Meloy was beguiled by Chaney's 2015 Nonesuch debut, The Longest River, an album incorporating traditional songs, classical pieces, and self-penned compositions that London's Guardian called an "enchanting, stately creation," and the Independent proclaimed was a "landmark release." As a performer, the New York Times has said that "Ms. Chaney is thoroughly grounded in the past… But in her quiet way, she's radical… no captive to tradition," stating that "whether she's singing old songs or her own, Ms. Chaney destabilizes them, turning them into rhapsodic, immediate dramas, giving listeners a reason to hang on every phrase and inflection."

"I had this idea that it was sort of a crime that she hadn't done 'Willie O' Winsbury.'" Meloy recalls. "I had heard Olivia's record and had been floored by it. I've spent a lot of time immersed in the sixties and seventies folk revival and was desperately trying to find similar things in contemporary music. Everyone is trying to put a novel or modern spin on arranging and interpreting these old folk songs. I found that Olivia was able to do that in a way that felt so organic and so true to the source material yet completely her own. It reminded me of Anne Briggs. I have a Twitter pulpit so I selfishly demanded that Olivia do 'Willie of Winsbury.' And that set off the conversation."

Chaney was in the midst of her album tour, sitting in "a grungy hotel in Brooklyn," when she saw Meloy's tweet. As Chaney remembers, "I sent Colin a private message back, thanking him, and said, 'If you're in town, I've got a lot of shows happening, come see me.' He said, 'Better still, come to Portland.' Within an hour, my booking agent and Colin's had arranged that I would support The Decemberists later in the year. The tour was fantastic, a wonderful experience. We were well looked after and the crowds were amazing—supportive, generous. Colin was very supportive too. Every so often backstage we would have fleeting but quite intense conversations about my material, thoughts about songwriting and singing traditional songs.

"One night, in Texas," she continues, "it was quite a harried gig; my guitar fell off in the middle of a song. That made the audience laugh, but I was a little shaky when I came off stage. Colin and drummer John Moen were watching and Colin said, grinning, 'Hey have you ever thought of having a backup band? We'll be your Albion Dance Band,'" referring to the ever-evolving electric folk combo that former Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span member Ashley Hutchings had formed in 1971 with several British folk luminaries, originally to back his then wife, the legendary vocalist Shirley Collins.

A year later, the band Meloy had been envisioning assembled for real at the Portland, Oregon studio of producer Tucker Martine. This pairing of Chaney with The Decemberists—Jenny Conlee, Chris Funk, John Moen, and Nate Query, in addition to Meloy—was dubbed Offa Rex, after a fabled British king from the eighth century. Martine had worked frequently with The Decemberists, as well as with Laura Veirs, My Morning Jacket, and Modest Mouse. He provided a welcoming, familial environment, his space crammed with musical instruments, vintage and new. The repertoire, the subject of many detailed email discussions between Chaney and Meloy, would be drawn almost exclusively from the canon of British traditional folk music, though Meloy did cajole Chaney into doing a version of Ewan MacColl's "The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face," written in 1957 for his wife Peggy Seeger and a pop hit fifteen years later for Roberta Flack. It was a wise move: Chaney delivers a breathtakingly naked performance—just voice, het harmonium, and unfettered emotion.

The Queen of Hearts is not merely an evocation of an earlier era, but a compelling hybrid, a beautiful collision, between this veteran indie-rock band and a singer for whom the living folk legends that Meloy admires from afar are often her fellow performers and friends. Offa Rex embrace the rousing, live-in-the-studio approach of folk-revival groups, especially on songs like "Blackleg Miner," on which Meloy takes the lead, and the instrumental medley of pub-worthy English Morris dance tunes, "Constant Billy (Oddington) / I'll Go Enlist (Sherborne)." The eighteenth century ballad "Sheepcrook" and its more contemporary Lal Waterson companion, "To Make You Stay," nod more overtly to the psychedelic side of the period; the former has a hint of metal in its arrangement while the latter, a duet between Chaney and Meloy, has a hypnotic, droning quality, created by Olivia's vocal layering and harmonium. And there are just plain lovely, heartbreaking tracks featuring Chaney's voice over some pared-down backing, like "The Gardener," which she wrote an arrangement for in London, alongside others, and "Flash Company," which came together on the final day of recording in Portland.

For Meloy, who has often taken to covering the work of artists he loves with The Decemberists, this was a fan's dream come true, playing the music he has studied and savored for years, a genre that has clearly influenced the chamber-rock sound of his band. For Chaney, however, this was both an intriguing and a daunting proposition. Chaney has long been a relatively self-contained artist, playing piano, guitar and harmonium, accompanied on tour only by a violinist. For years she was reluctant even to commit her voice to tape, despite a growing audience in the U.K. and Europe demanding an album. Born in Italy and reared in Oxford, Chaney has long resisted easy categorizing. Growing up, she was trained in classical piano but taught herself to play guitar and write songs; later she explored jazz as a student at the Royal Academy of Music in London; performed as a musician and actor at Shakespeare's Globe Theatre in London; and even briefly joined the trip-hop combo Zero Seven to be its touring vocalist. All the while she was building a formidable reputation as an artist in her own right in Britain, breaking boundaries in the folk scene and self-releasing a series of critically acclaimed EPs.

"For me this album was a massive learning curve," Chaney admits, "working with a band and being perhaps more 'trad,' not just in the folk sense but in the pop-rock sense. Here's a band, here's bass and drums—I don't think about music like that. It's not how I think about arranging traditional songs or my own songs. It was definitely a fun challenge. Once we had agreed to do the project, and sent song lists to and fro, I started to think about arrangements that would suit all of us. I had toured with the band and watched them play every night, so I felt I knew their musicianship. Some of our favorite tracks, certainly mine, were caught on the fly, Tucker and Colin really twisting my arm to go with the first take. That kind of nuts and bolts of making a record and working with more experienced guys in the studio... I knew I would learn a lot from them, and I did!"

Given the period they were evoking, Meloy and Martine decided to record to analog tape, a new experience for Chaney and a rare one for The Decemberists. Says Meloy, "I probably haven't done that for ten years—maybe when we did The Tain in 2004. We set out to do it all to tape, no Pro-Tools whatsoever, no computer whatsoever. We were doing tape edits, tape punches—if you screwed up the take, you had to start again. Recording to tape was not only something we were doing for sound, but also to have it inform the decisions, which is so much of what happened in the sixties and seventies. You couldn't isolate a vowel sound in a vocal take, take it out and re-record it. That would also lend to our general vibe. Olivia is a perfectionist and she was concerned about getting a vocal take better. But if it's good, you can't put it under the microscope like you would with Pro-Tools. You have to embrace the flaws. When I listen to the album now, I don't hear flaws. If you hear the very first Anne Briggs record, there are vocal imperfections all over that record, but they make it so much more organic and approachable and human."

The most traditional aspect of Offa Rex is perhaps the carrying on of tradition, of passing on songs musician to musician, from one culture to another. As Meloy reflects, "There's this weird relationship between British and American music, this interesting trade and theft that goes back and forth. My hope was that if we—the neophytes, the dilettantes, the pretenders—brought Olivia to Portland to work with Tucker, perhaps these traditional British songs would be infused with something different."

—Michael Hill