Argentine composer and pianist Fernando Otero found his voice as writer, musician and bandleader when, at the urging of one of his music teachers, he began to incorporate the indigenous sounds of his native Buenos Aires into his work. He was just a teenager then, but an exceptionally gifted one, a serious student of classical music with an ability to master a variety of instruments from a very young age. Otero had already begun to experiment with rudimentary home recordings and was eager to start writing on his own, though he gravitated more to a jazz idiom than a classical one. Otero liked popular music too -- often learning as much from the rock and jazz albums his older sister brought home as from his formal lessons – but he had given little thought to the gorgeous clamor around him.

As he recalls, a guitar and composition instructor, Marcelo Braga Saralegui “showed me the possibility of developing something with the roots of tango, the sound of tango. Not necessarily tango itself, but the music I heard as a child, the sound in the streets. I started working with a bandoneon player and tried my first project, which I called X Tango.”

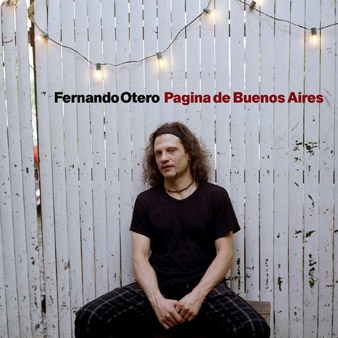

Twenty years have passed since Otero opened his ears to this wealth of ideas, and ever since he has pursued his vision of X Tango. On his Nonesuch debut "Pagina de Buenos Aires", he does evokes a feeling of Buenos Aires – something you can sense even if you’ve never been there --through his innovative use of the bandoneon, the accordion-like instrument at the heart of all tango. But the world Otero conjures up is really all his own. Tango is a jumping-off point for an instrumental sound that boasts the improvisatory thrill of jazz within a more formal, contemporary classical structure. In his last CD "Pagina de Buenos Aires", his work is often short, fast-paced and intense, full of enough dramatic stops and starts to astonish first-time listeners -- and confound any couple that might be fooled into thinking this is simply dance music.

As a composer, Otero is both rigorous and playful. His pieces at times echo the elegant nuevo tango of Astor Piazzola, but they also harbor a mischievous spirit that suggests Carl Stallings’ ingenious scoring for animated cartoons -- especially on tracks like “La Vista Gorda” and “De Ahora En Mas,” when piano, violin and bandoneon seem to be chasing each other around a melody. He counters this uptempo material with romantic interludes redolent of vintage film scores on tracks like “Asuncion” and “Calendario.” It’s no surprise that the always adventurous Kronos Quartet has commissioned a piece from him, scheduled to debut this fall.

Fernando Otero showcases the artist performing original material in a variety of formats: with a quintet of piano, violin, cello, acoustic bass and bandoneon; a trio of bass, bandoneon and piano; a duo, featuring long-time collaborator, violinist Nick Danielson; and on solo piano. The final two tracks are orchestral works conducted by Otero and featuring a 25-piece ensemble, plus band-mate Hector Del Curto on bandoneon. Though the majority of the work is new, a few pieces had previously appeared on Otero’s 2002 quintet session, Plan, released under the group name Fernando Otero X Tango. Taken together, these tracks illustrate the breadth, consistency and remarkable maturity of Otero’s vision.

“His music is very expressive, “ says violinist Danielson, a distinguished artist himself, who has performed with the New York City Ballet Orchestra and played the title role in the recent Broadway revival of Fiddler on the Roof. “It’s not easy to play. You have to play it with all your emotion.”

Otero has clearly focused his ambitions on his compositions, not the machinations of his career, which he has allowed to develop somewhat serendipitously. He relocated to New York City a decade ago, after brief stops in London and Madrid; Otero admits, however, that he was drawn here by a romance, not according to some master plan. He lives in a multi-ethnic Brooklyn neighborhood that has not yet experienced the gentrification happening merely blocks away. This bohemian refuge, teetering on the brink of change, more than suits him; it seems to reflect exactly where he stands as an artist.

While he remained unknown to the world at large, Otero had, for some years now, been a well-kept secret among jazz and classical insiders. His Plan CD has circulated among fellow musicians and attracted them to his recitals. Otero has composed and performed with several symphonies and chamber groups in the U.S. and Mexico, and has also written for ballet and theatre companies. Actress Salma Hayek introduced Quincy Jones to Otero at a Hollywood party; Jones subsequently arrived unannounced backstage after Otero performed a two-hour solo piano recital in Los Angeles, offering advice, encouragement and an open-ended invitation to do a project with him. (“It was as if Santa Claus had come backstage,” Otero jokes.) He has collaborated with one-time Bill Evans sideman Eddie Gomez, flautist Dave Valentin and pianist/film composer Dave Grusin, among others; he played with Chico O’Farrill’s Jazz Orchestra at jazz @Lincoln Center; and, most recently, he’s joined clarinetist Paquito D’Rivera on stage and in the studio.

“Last year,” says D’Rivera, “our trumpeter Diego Urcola called my attention to Nicholas Danielson and Fernando Otero, whom he holds in high regard. Intrigued, I attended a recital they presented in Manhattan. I was so impressed by what I heard that I invited the violinist to be part of my own concert at Jazz At Lincoln Center and asked Fernando to record his wonderful ‘Milonga 10’ with me on my first self-produced CD, Funk Tango. Even since, Fernando has become one of my favorite composers.”

Otero was reared in an environment steeped in music and the arts. His father, an actor, passed away when Otero was a year old; he was brought up by his mother, Elsa Marval, an internationally successful opera singer. His parents were first generation Argentines. His maternal grandparents had emigrated from Spain, where his grandmother had also been an opera singer; his father’s family had come from the South of France. As Otero recalls, “Music at home was very natural. We had a piano, and everyone was singing and playing --my mother, my sister, me. I didn’t even think about being a musician or not. I just was a musician. And I remember being a musician all my life. I never thought about doing anything else.”

Otero’s mother fueled his desire to master new instruments, absorb new ideas. He was studying piano and singing at age 5; guitar by the time he was 10. He also picked up the drums, accordion and melodica. Says Otero, “Whatever I requested from my mother that had a musical aspect – whether it was a teacher, a show, an instrument or a record – the answer was always yes.” She took him to hear symphonic music at the Teatro Colon, where she herself had performed, and that piqued Otero’s curiosity about playing with and composing for an orchestra. Among those who taught him as an adolescent was Domingo Marafiotti resident conductor of the Symphonic Orchestra of the Teatro Colon, with whom Otero took master classes in orchestration and conducting. Otero recalls, “The teachers were serious – and the price my mother paid for the lessons were serious too.” He admired Igor Stravinsky and, especially, Bela Bartok, whose music, he points out, also incorporated folkloric influences. As he explains, “They were representing their cultures and they were using their language to express themselves and that was very important to me.” The South American influences he cites were all virtuosos as well as iconoclasts,: Argentinian legend Piazzola, the Brazilian composer Egberto Gismonti and Uruguayan multi-instrumentalist Hugo Fattoruso.

Early on, the precocious Otero began to improvise his own recordings at home: “I liked to go into the bathroom where I could get a natural reverb sound. I had two cassette recorders that I used for overdubbing – it was all low quality, of course, as a result of dubbing and dubbing on two tapes and adding tracks in the bathroom with a guitar. I’d stay there, making music -- singing, playing guitar or small drums, whatever portable instruments I could get in there.” As he grew older, Otero learned how to navigate a real studio and he was often asked to produce and mix other local artists.

For many years, the young Otero thought he would become a singer; it was surely part of his musical DNA. He had vocalized at home when he was a child and later, he would front his first three bands. But instrumental music proved to be the most powerful way for Otero to channel everything he’d learned and wanted to express about his extraordinary upbringing, about the music that had shaped him, about Buenos Aires. Without singing a word, he discovered how to tell a story, and it’s one that has clearly just begun.

Michael Hill