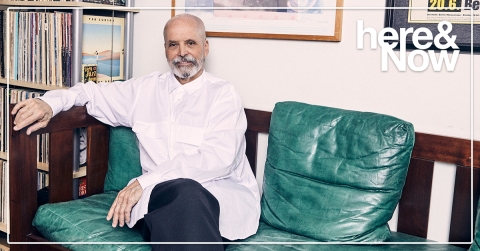

By Robert Hurwitz

Nonesuch Records President Bob Hurwitz shares his experiences visiting New Orleans' Lower Ninth Ward to present Habitat for Humanity with a $1 million check on the first anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. The money was raised from sales of Our New Orleans, the Nonesuch album celebrating music of the Crescent City, to aid in the creation of the neighborhood's new Musicians' Village.

From Bob Hurwitz to his Warner Music Group colleagues

A group of us from Nonesuch went down to New Orleans last Tuesday to present a check for $1 million to Habitat for Humanity on the first anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. I was with four of my colleagues from Nonesuch—David Bither, Karina Beznicki, Melissa Cusick and Eli Cane—all of whom gave up two months of their lives to work on this record. None of us fully understood the scope of this tragedy until we spent many hours driving around the city, seeing the Lower Ninth Ward and many of the neighborhoods that had been terribly damaged during Katrina.

We knew that making the album Our New Orleans and raising money was important and essential, but we had no clear picture of what it really meant until we actually came to the site of Habitat’s Musicians’ Village.

We arrived mid-afternoon on Monday, and went to the Village right straight from checking into the hotel. We had originally planned to drive around by ourselves, but when we arrived, we learned the hotel we were staying at was right next to the one where President Bush was staying. When we walked out of the door, we saw two-dozen secret service agents on the street, getting their instructions. The concierge warned us that if we drove out of the hotel, we couldn’t return in our car because of security concerns. So we arranged for the hotel to hire a professional tour guide named Ellen; this was the first “disaster” tour she had given since the storm

The first stop was at the Musicians’ Village, which is where the proceeds from the Our New Orleans album will go. The Village was conceived by Harry Connick, Jr. and Branford Marsalis, in collaboration with Habitat, to provide affordable housing for local working musicians and other low-income residents. Ground was broken on the site in June. It was sweltering, the way New Orleans always is in late August, but it was still a glorious day with high white clouds and blue skies. “The day before Katrina,” our guide said, “it was just like this. You never would know a storm was coming.” We were overwhelmed at how beautiful the Musicians’ Village looked. There was a lot of progress: it appeared that 30-40 homes were already constructed; the ones that were finished were painted in bright pastel colors, resembling the Caribbean style, which is such a big part of New Orleans culture.

The Village stands on a site where a junior high school had been torn down a few years earlier; it was the size of a couple of football fields, just a mile or so from the St. Claude Avenue bridge, which leads to the Lower Ninth Ward, the area that was utterly decimated during the storm and flood that followed when the levees broke.

When we arrived a half-hour later in the Lower Ninth Ward, it was hard to comprehend what we were seeing. There were the scattered remains of a few buildings, overturned boats and cars, fallen trees, trash and debris still in the street, and block after block there was nothing but grass growing over the foundations of houses that had been swept away. It was hard to believe that what now looked like an enormous empty lot was filled with houses just a year ago. There was nothing left: no signs of life, no people, no children, no habitable dwellings, nothing that would suggest that this used to be a vibrant and dynamic community.

Though New Orleans is in the Eastern US, the streets near the Musicians’ Village—still standing, but with few people moved back in—seemed to me to be more like the types of streets you might see in parts of in the center of Los Angeles, or in a small Midwestern town—modest one story, single-family houses, with front lawns, driveways, trees, backyards: not an affluent neighborhood, but good, solid housing, spread out with plenty of open space and sky. One could only imagine that the streets and houses weren’t that different in the Lower Ninth, just a mile away. But everything in the Lower Ninth was now gone, except for a few concrete steps leading to a doorway here, a fireplace there.

When our drive began in the mostly undamaged French Quarter, Ellen spoke optimistically about New Orleans and its chances for recovery, but as the afternoon went on, she told us about how she, like so many, had suffered greatly from the events of Katrina. She was putting up the best front she knew how, but, as she warned us, she might cry at any moment. She took us to a street where her brother and his family lived, near St. Bernard’s Parish. They lost their house, like everyone else on the street; they were now living in a FEMA trailer. She told us that on this one street, two people have committed suicide and three elderly people died in the last few months. Ellen and her husband, who lived in the suburbs, were also temporarily living in a FEMA trailer for a short time, but found the conditions so depressing and unlivable that they have moved out and are sleeping on the floor in the house of cousins, or sometimes in their daughter’s dorm at LSU. They had been told by the government that their house was salvageable, but workers are expensive and hard to come by, as is insurance reimbursement, so they didn’t expect to be home again for quite some time. Her husband, by the way, works for the Army Corp of Engineers.

As the trip went on, we all became more and more despondent about what we saw. When Ellen dropped us off, we realized that our first stop had been the brightest spot in New Orleans: the Musicians’ Village. What we had not counted on was that it was the only bright spot we would see in New Orleans. New Orleans had become a ghost town, and people we spoke with were full of despair—although most also had a stubborn bit of optimism in them, too.

We returned to the Musician’s Village the next morning, and felt cheerful again. We were greeted by more than one hundred volunteers, who had come to Habitat via Americorp and local church groups. Jonathan Reckford, the CEO of Habitat for Humanity International was there, as well as Jim Pate, executive director of New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity and Ken Meinert, senior vice president, Operation Home Delivery. Two of the musicians from Our New Orleans—Davell Crawford, who sang the incredible “Gather By the River,” and Spyboy Spider from the Wild Magnolias Mardis Gras Indians—were there, as were album producers and contributors Nick Spitzer and Matt Sakakeeny.

In presenting the check, I spoke of the hundreds of hands who touched this record, who created our own community in the process. The community included artists, engineers, producers, writers, photographers, caterers, studio owners, videographers. Many of them were in our own company. The Sunday after Katrina struck, Tom Whalley called me and asked my help in putting together a company initiative at Warner Bros. to help in any way we could. When I told Will Tanous of Corporate Communications how much I thought a benefit album would cost, I got an email back from him three minutes later telling me that Edgar Bronfman had approved the budget, and that WMG would cover the costs as a donation, which meant we would have that much more to give Habitat.

I called Mike Jbara at WEA and asked for help getting the best manufacturing prices we could from Cinram; he called back, and told me they had offered to donate a large number of units. Mike also made sure that the road was clear to turn the record around quickly, getting it out in days instead of the usual months. I called John Esposito, the head of WEA, and he immediately told me that they would absorb their distribution costs and donate their services. So far, we have sold more than 150,000 records around the world, and have given Habitat for Humanity a check for $1 million—that must be some sort of record in our business—and we will make further contributions as the album continues to sell. Tom, Hildi Snodgrass, Susan Genco, and Marc Cimino from Warner Bros. cut through every possible piece of red tape to clear the path for the recording, and to make sure we gave as much money from the purchase price as possible to Habitat.

Every drop of sweat at the Village has come from the labor of volunteers. Every dollar raised has been from donations like our own.

It has been a tremendous privilege for all of us at Nonesuch to be part of Our New Orleans, and it was deeply moving how our company rallied at the time of Katrina, in so many divisions, and at so many levels. But what we learned on our trip is that this disaster is far more profound than any of us can imagine, and in many respects, things are as bad today as they were a year ago. This trip made the five of us realize that the work is only beginning.

That said, last week once again demonstrated how much good can come from all of our collective efforts.