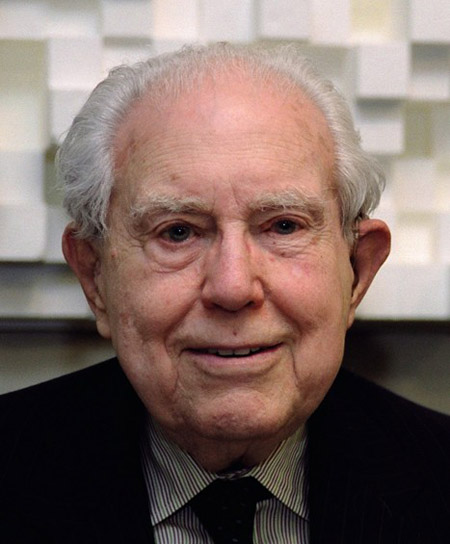

Nonesuch Records is saddened to learn of the death of American composer Elliott Carter, who passed away yesterday at the age of 103. In a career that spanned over 75 years, Carter composed 158 works and received two Pulitzer Prizes. In 2008, on the occasion of Carter's 100th birthday, Nonesuch released A Nonesuch Retrospective, a four-disc set featuring most of the recordings the label made of Carter’s music between 1968 and 1985, with a note by Paul Griffiths, which is reprinted in its entirety here.

Nonesuch Records is saddened to learn of the death of American composer Elliott Carter, who passed away yesterday at the age of 103.

Born in New York City on December 11, 1908, Elliott Carter began to be seriously interested in music in high school and was encouraged at that time by Charles Ives. He attended Harvard University where he studied with Walter Piston, and later went to Paris where for three years he studied with Nadia Boulanger. He then returned to New York to devote his time to composing and teaching.

In a career that spanned over 75 years, Carter composed 158 works ranging from early masterpieces such as Symphony No. 1 (1942) and Holiday Overture (1944), to Dialogues II (2012) which premiered on October 25 at La Scala, Milan. His work for chamber orchestra, Instances (2012), will receive its world premiere in February 2013 by the Seattle Symphony. Carter has received two Pulitzer Prizes and commissions from many prestigious organizations.

Carter celebrated his 100th birthday on December 11, 2008, at New York’s Carnegie Hall with a new work performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, one of the many salutes from performing organizations around the globe. That year Nonesuch released A Nonesuch Retrospective, a four-disc set featuring most of the recordings the label made of Carter’s music between 1968 and 1985. The set includes a note, printed in its entirety below, by former New York Times music critic Paul Griffiths, with whom Carter collaborated on his first opera, What Next?, in 1999; Griffiths wrote the libretto.

The New York Times, in its obituary by Allen Kozinn, details his early life and career trajectory; read it here. The Guardian discusses his relationship with his European audience; read their obituary here.

----

Elliott Carter: The Nonesuch Years

by Paul Griffiths

Born when Enrico Caruso was cutting cylinders, Elliott Carter has lived through most of the history of recording, and contributed to that history through his associations with various companies. First among these was Nonesuch, beginning in 1969 and continuing for over twenty years. Two albums of the 1970s, featuring his first two string quartets and Double Concerto, played a conspicuous role in carrying his music to a wide audience, and so in bringing him the acclaim that encouraged him to go on, with undiminished vigor, into a “late period” that has lasted more than thirty years. Nonesuch was not only the first label to give Carter’s music international distribution and continuing support, it also placed his work in an appropriate context of discovery and adventure.

Recording was one manifestation of the age of mass production that was arriving in many fields when Carter was born, in New York City on December 11, 1908. Carter belongs fully to that age, and his music still embodies the thrill of the revolutions that were its artistic counterpart: the overthrow of traditional harmony, the release from metrical rhythm, the search for new sounds, and—a revolution he made his own—the experience of different speeds simultaneously. Yet Carter’s music shows, too, an affection and even a moral respect for handiwork, for craft. Out of this tension, between making things new and having them well-made, has sprung his whole output.

Taking time to find himself, he published little before he was in his thirties, his earliest acknowledged works including several choral pieces and a symphony, as well as the delightful Robert Frost songs of 1942 featured here. The Elegy for Strings also belongs to this period, as it was adapted in 1952 from a 1943 composition for cello and piano. Change came with his Piano Sonata (1945-6), which, he has said, “was the beginning of a new trend in my music which was I should say, the gradual elimination of a definite scheme of tonality.”

Though Carter was still using key signatures, consonance in the sonata is not so much of tonality as of interval, with octaves, thirds, and fifths all strongly favored. These help give the piece its brightness, while the skirting of regular cadences keeps it always on the move. As the composer has pointed out, the music “wavers between two keys a semitone apart, and you never can tell which key it’s going to end up in, or where it goes.” Its mobility is also a matter of rhythmic fluidity, somewhat jazz-style, and of suppleness in how the basic melodic shapes are constantly being reinterpreted. As if pointing toward the later Carter, neither of the two movements is content with just one character. The first is a sonata-style dialogue between maestoso and scorrevole materials; the second begins and ends with music of slow chords, enclosing a dashing and imposingly extended fugue.

Carter continued and intensified the new spirit of his Piano Sonata in his ballet The Minotaur (1947) and his Cello Sonata (1948). The ballet’s lapidary, wind-heavy overture provides a one-minute introduction to a scene in which Pasiphaë, the wife of King Minos of Crete, prepares for a tryst with a white bull. Some of her servants blow horns to summon the bulls, and she dances with her fearsome mate. The curtain falls on the sound of her breathing, and the interlude for the change of scene ends with a recollection of the overture.

The pulse of Pasiphaë’s post-coital respiration comes back as the hammering of the masons who are building the labyrinth that Minos has ordered, in which to imprison his queen’s fearful bastard: the Minotaur. With swaying string music, and a further recall of the overture, Minos appears, accompanied by his and Pasiphaë’s daughter Ariadne. They oversee the selection of captive Greeks—among them the hero king Theseus—who will be sent into the labyrinth for the Minotaur to devour. There follows a pas de deux for Ariadne and Theseus, a delightful allegretto for slimmed orchestra with solos for flute, violin and, later, cello.

Trumpets, trombones and percussion re-enter at the start of the next section, an image of the labyrinth, in which the same brute fanfare seems to show the Minotaur reflected everywhere. Then Theseus takes his leave of Ariadne to an andante for strings, given a varied reprise with woodwinds to the fore. Ariadne, to another gentle movement, unwinds the thread that Theseus takes with him into the labyrinth, so that he will be able to find his way out again, the thread of a line starting out on solo clarinet.

Weight returns for Theseus’s battle with the Minotaur, who is pictured as before. Ariadne’s rewinding music is like that of her unwinding, but the thread breaks, and the tension in the musical line slithers up and away. A short lament follows, but there is no catastrophe: to an allegro, with jazzed rhythms, Theseus and his party come safely out. The finale, of preparing for departure, works from a counterpoint of rhythmic streams toward a grand peroration and a return once more to the severe strains of the overture, this time brought to a firm conclusion in E major.

The four-movement Cello Sonata marked a further decisive step in Carter’s self-allotted task of increasing Western music’s rhythmic variety and freeing its form. For rhythmic ideas he studied a lot of non-Western music—Indian, Arab, Balinese, African—as well as fourteenth-century polyphony and Henry Cowell’s book New Musical Resources, not to mention jazz. As for form, he wanted “change, process, evolution as music’s prime factor.”

The fact that he was writing a cello sonata also helped, for it provided him with a medium in which two unalike instruments could offer different experiences of time. “So,” he notes,

the opening Moderato presents the cello in its warm expressive character, playing a long melody in rather free style, while the piano percussively marks a regular clock-like ticking. This is interrupted in various ways. The Vivace, a breezy treatment of a type of pop music, verges on a parody of some Americanizing colleagues of the time. Actually it makes explicit the undercurrent of jazz technique suggested in the previous movement by the freely performed melody against a strict rhythm. The following Adagio is a long, expanding, recitative-like melody for the cello, all its phrases interrelated by metric modulations [i.e. changes of speed engineered by switching the meter while the pulse for the moment remains the same]. The finale, Allegro, like the second movement based on pop rhythms, is a free rondo with numerous changes of speed that end up by returning to the beginning of the first movement with the roles of the cello and piano reversed.

Continuing the innovations of his Cello Sonata, Carter’s next major work was his First Quartet, which he composed in Arizona in 1950-51, in deliberate retreat from New York, and about which he wrote illuminatingly for the 1970 Nonesuch release:

Like the desert horizons I saw daily while it was being written, the First Quartet presents a continuous unfolding and changing of expressive characters—one woven into the other or entering from it—on a large scale. The general plan was suggested by Jean Cocteau’s film Le Sang d’un Poète, in which the entire dreamlike action is framed by an interrupted slow-motion shot of a tall brick chimney in an empty lot being dynamited. Just as the chimney begins to fall apart, the shot is broken off and the entire movie follows, after which the shot of the chimney is resumed at the point it left off, showing its disintegration in mid-air, and closing the film with its collapse on the ground. A similar interrupted continuity is employed in this quartet’s starting with a cadenza for cello alone that is continued by the first violin alone at the very end. On one level, I interpret Cocteau’s idea (and my own) as establishing the difference between external time (measured by the falling chimney, or the cadenza) and internal dream time (the main body of the work)—the dream time lasting but a moment of external time but, from the dreamer’s point of view, a long stretch. In the First Quartet, the opening cadenza also acts as an introduction to the rest, and when it reappears at the end, it forms the last variation in a set of variations.

The “continuous unfolding” means that the four movements of a common pattern—strenuous argument, scherzo, adagio, and relatively frolicsome finale—are linked, and then broken apart again in different places, so that the scherzo has already established itself before the first pause comes and the finale is in train when the second arrives. Of a piece with this complex flow is the detail: the rich harmonic world, the profusion of characters and incidents, often in open dispute, and the conception of the four players, especially in the first movement, as resolute individuals. Much of this opening movement strides forward powerfully through the tussle of four-part writing in which each part has its own rhythmic style, its own manner of speaking. When this movement becomes more thoroughly becalmed, from it emerges the scherzo. The adagio divides the quartet into two duos: violins playing the music of heaven, and viola and cello earthier, intemperate. Eventually, perhaps tired of objecting to the violins’ unworldliness, the two low instruments join them, but only for a short while. In the finale may be heard Carter’s feelings for jazz, compounded with much else.

With this breakthrough piece, Carter established not only a new style but also a new pattern of composing. For the next quarter century, he was to concentrate on big instrumental forms slowly achieved, beginning with his Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello, and Harpsichord (1952) and Variations for Orchestra (1955). The Sonata takes the lineup of a Baroque trio sonata and has it engage in the kind of group dialogue heard throughout the First Quartet. Though the succession of movements, fast-slow-fast, is more traditionally presented, the instruments have their own personalities and will often go their own ways, with their own kinds of rhythmic and harmonic behavior.

The Variations, Carter has said, are based on “a more dynamic and changeable approach” than was customary for the form. There is a principal idea, but it undergoes such great changes, and is sometimes so much confronted with other material, that the sequence of nine variations plus finale is swept into a continuous flow. Contrast, abundant at first, is progressively reduced toward the fifth variation, from which point conflict is renewed as the main theme struggles to define itself, eventually being restated by trombones.

Carter then returned to the string quartet for another breakthrough. Completed four years after the Variations, in 1959, his Second Quartet apparently required two thousand pages of sketches. The result was a piece in which the instruments are thoroughly individualized, in terms especially of how they move, and in which there are no themes but rather groupings of intervals that can be constantly redisposed. The instruments are, as it were, the themes, and the music is their dialogue, a play expressed in wordless challenge, dispute, concession, arbitration, and unstable concurrence. This is, more or less, how all Carter’s music has gone ever since.

The composer notes in the score that the first violin “should exhibit the greatest variety of character, sometimes playing with insistent rigidity but more often in a bravura style,” contrasting with the second violin part, which is “mostly written in regular rhythms.” The viola, different again, is “predominantly expressive,” while the cello gains its character from its habits of accelerating and decelerating. The work’s introduction sets out these identities, and shows too the harmonic contrarieties on which they partly depend, with different intervals coming to be sustained in each part: fifths and minor thirds (violin I), major thirds, sixths and sevenths (violin II), diminished fifths and minor sevenths (viola), and fourths and minor sixths (cello).

From here the work proceeds continuously, through a normal sequence of four movements (resembling that of the Cello Sonata), if without much sign of normal forms. Each movement is led by one of the instruments, in descending order through the ensemble, and each is linked to the next by a cadenza for the instrument that will have the dominant role two movements ahead. The cadenzas also serve to effect the gear change from one movement to the next, so that, for example, the viola has to struggle somewhat with its songful nature in making the move from the opening allegro to the scherzo. Conversely, the first violin’s cadenza, unlike the others in being largely unaccompanied, is fully in keeping with its virtuoso character. The cello at the end is the extrovert peacemaker, but, as the conclusion reveals, the essential harmonic differences remain.

Carter then moved rapidly on to his Double Concerto, completed in August 1961, an exuberant turmoil of notes, colors, speeds, and directions. Its constant change he associated with the vision of the Roman philosopher-poet Lucretius, who saw a universe in which everything, everywhere is in movement:

All things keep on, in everlasting motion,

Out of the infinite come the particles

Speeding above, below, in endless dance.

But this is also a contemporary vision, and Carter, as a keen observer of scientific developments, could have had in mind images of subatomic particles streaming, colliding, conjoining, disintegrating, or of stars and galaxies in perpetual evolution.

Something else keenly at issue in the early 1960s was the fate of humanity. The testing of multi-megaton hydrogen bombs and the development of rocketry had created conditions of unprecedented danger, in the light of which—dark of which, one might say—may be understood Carter’s second declared literary connection, with lines from Pope’s Dunciad:

Nor public flame, nor private, dares to shine;

Nor human spark is left, nor glimpse divine!

Lo! thy dread empire, Chaos! is restored;

Light dies before thy uncreating word;

Thy hand, great Anarch! let the curtain fall;

And universal darkness buries all.

Perhaps it is significant, too, that this concerto is a double one, a work for two rival blocks, differently constituted and working to alternative principles. The goal is unity, but it is achieved only after the unleashing of tremendous force—the force, surely, of the great Anarch’s Chaos. Yet though we seem to be left at the end with ashes and obliteration, the music retains its lightness, even its gaiety.

The two blocks are distinguished in various ways, as the composer has explained. Not only does each have its own soloist, but the surrounding ensembles are distinct and yet parallel, evenly matched. The harpsichord is accompanied by two percussionists playing mostly wood and metal instruments, with two string players on viola and double bass, and a foursome of blown instruments comprising brass trio and flute, whereas the piano has two percussionists favoring skin drums, with violin and cello as string representatives and a wind quartet of oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon. Each nine-piece outfit has its own repertory of intervals and so of chords, and also its own kinds of rhythmic movement. The result is, in the composer’s words, a divergence of “musical characters, gestures, logic, expression, and ‘behavioral’ patterns,” but all of these also tied across the divide in changing ways as the music moves in ceaseless flow.

Though continuous, the piece proceeds through several phases, beginning with an introduction in which notes, chords, and shapes gradually emerge from a light mist of percussion and the double play begins. A burst of strong, contradictory impulses from the two groups introduces a cadenza for the harpsichord, followed soon, after a pause, by an allegro scherzando, in which the piano group has the main role and the harpsichord group offers “brief interruptions and comments.” Then, gradually slowing, the music arrives at an adagio, whose steady pace is maintained largely by the eight winds, while the others come and go in accelerating and decelerating waves. Towards the end of this sequence comes a duet for the soloists, both in rapid figuration—a moment of alliance (though in different meters) broken when the piano accelerates away and the harpsichord falters. The ensuing presto balances the allegro scherzando, in that this time the continuity belongs with the harpsichord group; the piano, indeed, is silent. This chapter, though, is short, and is succeeded by a pair of piano cadenzas. Conflict is then resumed, resulting, after another pause, in the big bang and wind-down of the coda.

The soloists on this classic recording, Gilbert Kalish and Paul Jacobs, were among the four musicians for whom Carter wrote his second big solo piece for piano: Night Fantasies (1980), an involuted nocturne to counterweight the bright day of the Piano Sonata. The music suggests, in the composer’s words, “the fleeting thoughts and feelings that pass through the mind during a period of wakefulness at night,” the quiet opening being broken by the first of many episodes “of contrasting characters and lengths that sometimes break in abruptly and at other, develop smoothly out of what has gone before.”

Night Fantasies interrupted a trilogy in which Carter returned, after more than three decades, to song, a trilogy he completed with In Sleep, in Thunder (1981), in which a tenor sings poems by Robert Lowell—three having to do with personal relationships, three with religious belief—with support and contrariety from an ensemble of fourteen players. “What attracted me about these texts,” the composer wrote, “were their rapid, controlled changes from passion to tenderness, to humor and to a sense of loss.” He added that, “as in other recent scores, I have tried to write music of a continuous but coherent change, which to me is the most evocative kind.”

So it was in his next work, Triple Duo (1982), which is perhaps the first of his compositions in which the wordless dialogue is essentially comic. Following the principle of his First Quartet’s adagio and the whole of his Third (1971), Carter divides the group into conversing pairs: flute and clarinet, violin and cello, piano and percussion—though there is room, too, for individual flights of fancy. Now all the qualities of Carter's extraordinary late period, playful and expressive, were set up.

- Log in to post comments