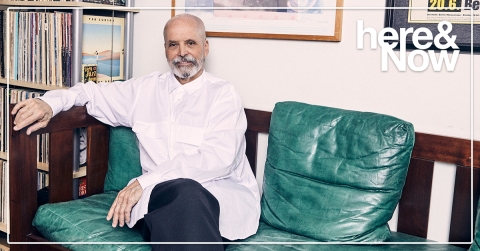

David Littlejohn, who taught journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, for 35 years, died at his home in Kensington, California, on June 4. He was 78. Littlejohn published some 400 works—reviews, profiles and critical essays—and 14 books in his lifetime. He also worked on the arts program Critic at Large, which aired on PBS stations across the United States. Nonesuch Records President Bob Hurwitz, who was a student of Littlejohn’s at Berkeley in 1971, offers this remembrance.

David Littlejohn, who taught journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, for 35 years, died at his home in Kensington, California, on June 4. He was 78. Littlejohn published some 400 works—reviews, profiles and critical essays—and 14 books in his lifetime. He also worked on the arts program Critic at Large, which aired on PBS stations across the United States. Nonesuch Records President Bob Hurwitz, who was a student of Littlejohn’s at Berkeley in 1971, offers this remembrance.

The assignments included writing a review of a new film (Five Easy Pieces); a review of the new installation of Hans Hoffman paintings at the recently opened Berkeley Museum of Art; a review of a recently published book about Vietnam (the war was still going on); a review of the production of Mozart's Così fan tutte at the San Francisco Opera.

The class was David Littlejohn's seminar in arts criticism, which I took in the winter quarter of 1971 at UC Berkeley. Though music was the thing I thought about every waking hour, Così fan tutte was the most irritating assignment of them all. I did not have the patience for either the production or the pretension of the audience, and rather than treat my essay with the same level of seriousness that I attempted with the others, I decided to write a personal screed—nasty, ill-informed, pathetically trying to be clever. Today you might call it snarky: sarcastic, critical with a mean edge. I was immature; I was far more in love with my own embarrassing and naïve ideas than what was in front of me on the stage.

Though I cannot remember all of David's written response, I remember the tone—surprisingly generous, without impatience or condescension. Bemused. He ended his comments by writing, and I paraphrase: "by the way, that production was one the two best things I saw all year. The only thing comparable was the Rolling Stones show at the Oakland Coliseum."

David Littlejohn passed away earlier this month. His class was unquestionably the most important one I took in school—at any level. I left the class in awe of both his tremendous knowledge and his endless enthusiasm about the arts and took with me many important lessons that changed the course of my personal and professional life.

For the last three decades I have been the president of Nonesuch Records. One of the things that I have tried to do in that position is not to be locked into one genre of music or another, to treat, say, a composer like John Adams, a classical singer like Dawn Upshaw, or a jazz musician like Brad Mehldau, no differently than a pop singer like k.d. lang, a Brazilian song writer like Caetano Veloso or a rock band like The Black Keys.

David's lesson—Mozart and the Rolling Stones—was the first time I had ever even thought about music of such diverse background possibly being discussed in the same sentence. Years later, after he and I were together at a Cal Alumni event in LA, he wrote to me, "I have been hopelessly eclectic (I hate all the pigeonhole categories dreamed up by music critics and musicologists) since 13, when I simultaneously fell in love with classic country and opera: I saw Hank Williams live three times before he died, and chased Maria Callas around Europe during my semester off in '57. I've been to every Bay Area Rolling Stones concert, heard all of John Adams live either in SF or LA, and fell all over again for bluegrass after O Brother Where Art Thou? and T Bone [Burnett]'s Down from the Mountain concert that followed."

Before David's class, I had liked lots of different genres of music, but I always thought they needed to be in separate boxes. It was like one of those lessons I had when I was younger taking piano lessons; I did not consciously act on it immediately, but it stuck somewhere in my consciousness, only to later to be retrieved in a meaningful way. It is one of those deeply appreciated lessons we are given in our youth that are so powerful that they inevitably become a fundamental part of our character.

And then there were the assignments. One of the things I have found working with many gifted artists is the very best are filled with curiosity, and can talk, quite knowledgably, about an unusually wide-ranging range of subjects—about literature, film, art, science, religion, an endless list. David's class was the first time I had to start looking at the arts, outside of music, with a more critical and informed eye, and the more I began to look at film and dance and art and other arts more critically, my understanding of music expanded exponentially.

David and I bumped into one another a few times over the years, but we really reconnected about a decade ago at the Cal Alumni event, and for the next several years continued to write to one another, primarily about our musical enthusiasms. The last time I saw him was two summers ago, for lunch in San Francisco, when he talked about his family, his career in television, both national on PBS (he would leave Berkeley to fly to Washington, DC, to tape the show every Friday and come back Monday to teach) and locally (he did at least 150 local arts shows on KQED; "almost none of it remains; they re-used the film"); the new projects he had hoped to launch into (a book about Burning Man, a book about John Adams—"except I can’t finish it because he will still be writing music when I write it"), the fate of critics ("Well, in the end, nothing I have written as a critic will matter anyway, because outside of George Bernard Shaw and Pauline Kael, almost no critic is ever remembered or read after they die." In David’s case, I’m sure this will not be true.).

He was also quite open, for the first time with me, about the terrible accident of his youth, when he broke his neck while diving in a lake, that left him unable to walk without crutches when he was my instructor, and in a wheelchair for the later part of his life. And what was so astonishing was that even from his teenage years he was able to show such an extraordinary and deep appreciation of life, and the beauty of life that can be experienced in great art. Many people have been broken by the terrible accidents or tragedies of youth; instead he seemed to have become one of the most optimistic and curious people I have ever met, and his enthusiasms for things of beauty—in music, in literature, in film, in architecture—was filled with delight, and seemed boundless. Another lesson, not about art, but about life; how could you not be completely taken by this man.

Growing up I had one other teacher who had a tremendous impact on my life. She was my piano teacher, Zlata Fay, a serious and highly intelligent musician, a woman of some mystery who escaped from Europe during the war. She never let on very much about her personal life, but she was a profoundly deep musician. I studied for more than a decade, but as a young boy and a teenager, never fully grasped what an extraordinary person she was; only in my 20s, when I came back for lessons whenever I returned to my family's home in Los Angeles, did it become clear to me how much I had missed in my youth. One night, quite casually, my aunt mentioned that she had died in the last year. I was stunned, deeply saddened, very few deaths affected me like this. I have continued playing the piano for more than three decades since she died. I still often think, when working on a new piece, how much I would have loved to have had the chance to play it for her.

With David it was a blessing I have no such regrets. In 2005 I wrote to him, after the Berkeley event. After recalling the Mozart incident, I wrote,

I was quite serious when I commented from the stage how important your class was. It was one of those building blocks I was able to use in my life, in terms of how I thought about art and culture, and more specifically, how I thought about music. Before then, I had an intuitive grasp of how things could relate to each other, but I had never connected the dots, and had rarely allowed myself to be open to things outside my then extremely limited world. Mozart, Rolling Stones—could they be part of the same discussion? From that point forward, they were.

And I added:

If you go to our website, and you find something from the Nonesuch catalogue you would like (Caetano Veloso's library or the DVD's we released of Balanchine or our Explorer Series reissues), feel free to let me know. I could happily send you the whole the catalogue, and it still couldn't come close to repay all that I got from being in your class.

- Log in to post comments