The legendary producer John McClure passed away at his home in Vermont recently. McClure produced countless recordings for Columbia Records, including many famed recordings with Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and Igor Stravinsky; led the Columbia Masterworks label; and produced or engineered several albums for Nonesuch Records, working with John Adams, Dawn Upshaw, Mandy Patinkin, Audra McDonald, and others. Nonesuch President Bob Hurwitz offers this remembrance.

The legendary producer John McClure passed away at his home in Vermont recently. McClure produced countless recordings for Columbia Records, including many famed recordings with Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and Igor Stravinsky; led the Columbia Masterworks label; and produced or engineered several albums for Nonesuch Records, working with John Adams, Dawn Upshaw, Mandy Patinkin, Audra McDonald, and others. Nonesuch President Bob Hurwitz offers this remembrance.

When I started collecting records as a teenager I probably bought more albums produced by John McClure than anyone else, though I did not know it at the time. I didn’t even know what a record producer was, and while I was buying up dozens of McClure-produced recordings, I did not make the connection that his name was on every album on Columbia by Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and Igor Stravinsky. What I did know was that I loved the wonderful performances of The Rite of Spring and Petrushka conducted by Stravinsky, and Bernstein’s Mahler Fifth and Beethoven Seventh Symphonies, and so many more. They were all vivid and powerful albums, and they made a profound impression on me during the years when I fell in love with recordings. Records were magical objects for me, and so many I heard at that age deeply affected me, ultimately drawing me into the business itself.

Only later did I realize that John McClure not only produced these recordings, but also ran Columbia Masterworks during its golden age, when it was the leading classical—one might add creative—record company in the world. And I began to understand that what I loved about those recordings was not only the music and the performances, but also their tremendous warmth, and clarity, and their energy, which was apparent to me even when I listened to them on the kind of inexpensive and not very sophisticated late-’60s stereo that a typical college student like myself owned.

The early 1980s brought to the public not only the CD, but also a revolution in the way albums were made, as there was a mad rush, especially in the classical world, to sweep away the old analogue magnetic tape machines for the new high-tech innovations of digital recordings. Many of us, especially in the early years, were quite disappointed about how remote and thin many of the first CDs sounded. Then one day, I heard a new recording that Leonard Bernstein had made of the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, which John had produced; it had all of the vivid characteristics of McClure’s great analogue recordings, and I thought, maybe it won’t be so bad after all. It was the first digital recording I heard that gave me the same feeling I had listening to my old vinyl LPs. And I remember thinking, it isn’t just a problem with the technology, it’s a problem with producers who haven’t figured out what to do with the technology. John clearly had.

John had tremendous insights into both the musical and the technological aspects of recording, but when you were with him, even in the studio, he never let it on. He never put himself ahead of the composer or the performer, as many other classical producer and engineers did. John had both an affable and unflappable nature that simultaneously created a kind of ease and seriousness in the studio. Though he clearly knew practically everything there was to know about engineering and the technology of recording, he kept an easy-going façade that put musicians at ease, helping them create their best performances in the always difficult circumstance of recording under time pressure.

By the time I first began working with him, not long after I started at Nonesuch in the mid-’80s, John was entering a new stage of his career. When Goddard Lieberson quietly moved away from Columbia in the mid-’70s, the company drifted from the high ideals it had established, and began to be a more ordinary label. “Best of” records and crossover hits became more of a priority. John once told me that when he was at Masterworks, the company lost money on 90% of the 50 records it put out each year. “I sometimes thought Goddard had a pop division in order to support Masterworks.” By the mid-’70s, the company started a succession of new heads coming in for a few years at a time, none of them staying long enough to create a coherent vision, and Masterworks was never the same. John no longer had any influence on the direction of Masterworks, and his activities there were largely limited to supervising the transfers of records from LP to CD.

But John found another outlet for his talents. He soon became extremely busy with television projects, with Lenny in Vienna and André Previn in Pittsburgh, and beginning a long and fruitful relationship with PBS—including broadcasts of the Boston and Cincinnati Pops, Robert Shaw in Atlanta, the opening of the Benaroya Hall in Seattle, and the re-opening of Severance Hall in Cleveland.

And he was still producing records. So it was wonderful to find out that this great man, one of my heroes in the record business, was willing to work on a Nonesuch project. Not long after I started at the label, I began supervising the second recording of Teresa Stratas singing Kurt Weill. The first sessions were kind of disastrous; things did not work out with the original producer, Eric Saltzman, and when I asked John to take over, he jumped right in. But the sessions weren’t easy for any producer, and a few days into overdub sessions with John, he quit. I was shocked. Stratas was not an easy person to work with, and John could sense after a few days it wasn’t going to work for him.

I was pretty naïve in my early years at Nonesuch, and I got too caught up in the project; I thought we were in the midst of making one of those transformational albums that would have widespread commercial and critical appeal. I was at the point where I was new in this part of the game, and I got too close to the production—this often happens not only in music, but in filmmaking and Broadway shows, where you are so deeply engaged in a production that you think that of course everyone in the world is going to see this in the same way that you do. (I sometimes still suffer from this disorder.)

And so I said to John, “How could you possibly quit? This could be one of the most important records of the decade!”

Politely he replied, “I’ve already made 50 of those kinds of records, and I’m not going to go through this aggravation just to make the 51st.”

John said goodbye, and I was left without a producer (that’s a story for another time), but our relationship began to blossom from that moment forward. He was involved in over a dozen Nonesuch projects, both as an engineer and as a producer, many of which were defining albums for us, including John Adams’s opera The Death of Klinghoffer, Leonard Bernstein’s New York, and the record production for both the album and the film of George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker. More importantly, we became good friends.

Not long ago, John’s old company Columbia started re-issuing boxes of their classic Bernstein albums in their original sleeves at what seemed to me to be ridiculously low prices—a box of ten could run between $20 and $25, and I snapped up four of them: his complete Mahler cycle; the six discs of Haydn’s music; a box of all of Bernstein’s compositions; a box of a potpourri which showed Bernstein’s range as a conductor, leading works by Copland, Ives, Sibelius, Haydn, Beethoven, Mahler, and others. These weren’t vinyl discs, and I don’t have the massive ADS speakers I had when I was young and single (as so many of us had), but whether heard through my car speakers, or my computer speakers, or any variation thereof, there was a kind of presence and liveliness in these recordings that I remembered from the time I didn’t know who was producing them. Though I know that the relationship between John and Lenny was not always comfortable for John, he really was the perfect producer for Bernstein—he found a way to create a sound picture that seemed to capture both the emotion and profound intelligence and humanity of these unforgettable Bernstein recordings.

The week John passed away was the week that there was a tremendous amount of attention in the media over the cancellation of the broadcast of John Adams’s opera The Death of Klinghoffer. As it has happens, John McClure produced the recording of the piece for Nonesuch in 1992 in Lyon, with Kent Nagano. The record holds up wonderfully today, and I know how much both John A. and John M. loved working together. One day after a session, John Adams and I were having dinner, and he related something John McClure had said earlier that day. “I had the great privilege of working with Lenny, and Stravinsky, and Copland, but now they are all gone. But now, I get to work with John Adams.”

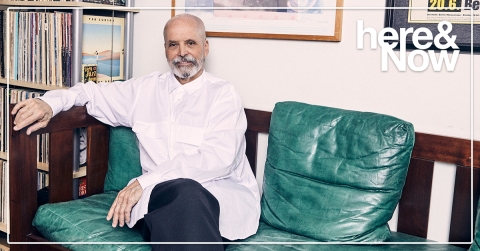

John was a tall, whimsical, brilliant, flexible, utterly endearing man. He was generous to all—he would always be extraordinarily generous with young engineers and producers, and would always share any of his ideas to anyone who asked. I never knew how old he was, until he passed away. In later years, a world-weariness could slip in on occasion, but most of the time I was around him—always with his wonderful wife Sue—I felt I was with a very young man. He ran Columbia, and produced Lenny, Stravinsky, et al., when he was in his 20s; and after his days running Masterworks, he had a perfect life, coming to New York to work on new recordings or record shows for PBS, sometimes supervise the CD reissues of albums he had made, and then head back to his home in Vermont, where he and Sue rode motorcycles and harvested maple syrup. We should all be so lucky.

—Bob Hurwitz

- Log in to post comments