"They were both fearless, pushing back against the severe music that seemed to dominate the modern composition landscape during the 1960s and 1970s, the same music that was, by the way, a major part of Nonesuch’s identity during that period," writes Nonesuch Records Chairman Emeritus Bob Hurwitz, in a remembrance of composers Louis Andriessen and Frederic Rzewski. "Neither was afraid to reference vernacular music, and jazz, and popular and folk music, and most importantly, both embraced a tonal language that was out of favor at the moment they were coming of age as composers. Their music was deadly serious at times, and polemical and political, but it could be humorous, and always filled with humanity."

By Robert Hurwitz

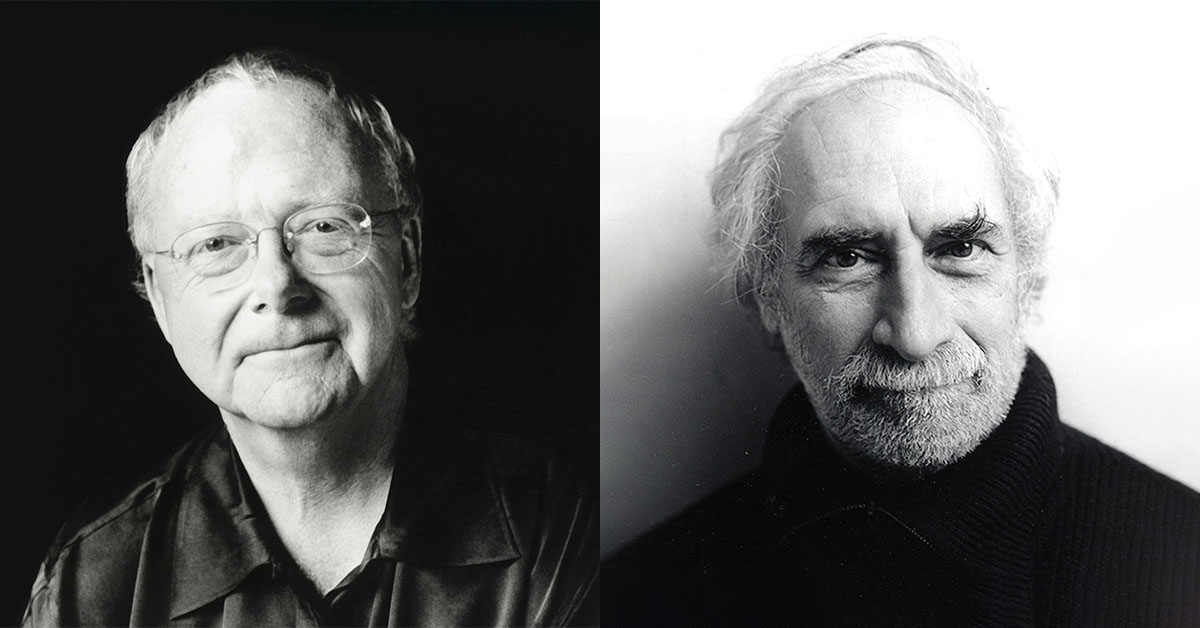

Louis Andriessen and Frederic Rzewski were born within a year of one another and died six days apart. Louis was Dutch, Frederic was American—though he spent much of his life in Europe—and they were among the most accomplished composers on the planet during their lifetimes.

Before they died, I never thought about them in relation to one another. But over the last several days, I’ve realized that what appealed to me in their music was, in fact, something quite similar.

They were both fearless, pushing back against the severe music that seemed to dominate the modern composition landscape during the 1960s and 1970s, the same music that was, by the way, a major part of Nonesuch’s identity during that period. Neither was afraid to reference vernacular music, and jazz, and popular and folk music, and most importantly, both embraced a tonal language that was out of favor at the moment they were coming of age as composers. Their music was deadly serious at times, and polemical and political, but it could be humorous, and always filled with humanity.

They were both extremely knowledgeable about the music of the past, and often referenced it in their own music. Rzewski’s deep love of Beethoven and Schumann was central to his music, as Bach and Stravinsky were at the core of Andriessen’s. They wrote original modern music that I genuinely loved, emerging at a moment when a lot of modern and contemporary music was “interesting” and “serious” and “important,” but in the end, quite difficult to like, not to mention love.

I first heard Rzewski’s music in the 1970s when I attended a concert of Ursula Oppens playing The People United Will Never Be Defeated. I was shocked in the best possible way—an hour-long piece I loved from the very first moment, music that sounded modern but also made me think of music of the past (especially Beethoven’s many sets of variations), that had the spontaneity of improvisation, that seemed perfectly constructed, that had me on the edge of my chair until the very end.

I was working for ECM Records at the time and called Manfred Eicher, who owned the company and produced practically all of its records; I set up a meeting with Ursula the next time he was in New York. I was thrilled that Manfred agreed to make a record. He offered her a modest advance, but then she never heard from him again.

A few years later I was at Nonesuch, and Frederic was on the short list of composers I hoped to record. I invited him for a meeting. It did not go well; he seemed suspicious of why I wanted to make records with him.

I remember thinking: I made two efforts to become involved with his music; for one reason or another, it may not be meant to be.

But about fifteen years later I was approached by the French producer Marc-Henri Cykiert, who had just finished producing seven records of Frederic’s music, all first-rate compositions, and all amazing performances by the composer. We quickly came to an agreement and a year later we released the seven-disc box of his music. It was a delight working with Frederic (and Marc-Henri) as we prepared for the release. It only took a quarter century of trying to have a professional relationship with Frederic, but I was grateful to have the opportunity to work with him and have Nonesuch be able to represent his work.

///

Both John Adams and the music critic Peter G. Davis told me about Louis Andriessen’s De Staat. John had conducted it in San Francisco and commissioned another new piece from Louis; Peter had heard a recording produced in Holland. I found a copy of the disc and immediately understood John and Peter’s enthusiasm. My reaction was similar to that when I first heard People United. I was able to track Louis down and he put me in touch with the wonderful conductor Reinbert de Leeuw and the manager of the Schoenberg Ensemble, Rosita Wouda. They suggested that besides recording De Staat, we might consider another of Louis’ pieces, De Tijd, that was ready for recording. In a move that would foretell our future dealings with Reinbert, Rosita, the Schoenberg Ensemble, and the larger Dutch new music community, they said they would record both of the pieces for the same price as just doing De Staat.

The participation of Reinbert and Rosita continued to be critical through the years. Louis’ records, sadly, never sold particularly well, and they were aware of it, so for every subsequent production, they cleverly found a way for us to get involved. The quality of the performances and the recordings were always sensational, no matter what the budget was. Reinbert, who conducted the first eight Andriessen albums we released, died early last year; Louis’ final album, The only one, was conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen and performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

This devotion to Louis from his musician friends was unprecedented in my time at Nonesuch. Imagine: three operas, the massive De Materie, all came out of Holland. The last two Andriessen albums were produced in association with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; like our Dutch colleagues, Chad Smith of the LA Phil and the orchestra found a way to make these recordings possible.

This relationship between Louis and the musicians who were part of his community was a central part of his artistic life, one that I grew to deeply respect even though it was the cause of some frustration in terms of my hopes that his music might be heard more frequently in the United States. From a journal entry, May 1996:

I am at lunch with Louis Andriessen, his wife Jeannette, and Carol Yaple of Nonesuch. I have practical considerations on my mind: how to get his music better known in America. I speak about the fact that orchestras find it very hard to play pieces like De Staat, not because it is too difficult to play, but because they have to hire the entire orchestra, plus extra players, even though most of the standing members of the orchestra won’t perform. Would he consider adapting pieces, to help make them more likely to be performed by American orchestras? He says, “You know, in Holland, I am lucky to be subsidized by the government, and so I am less concerned with making money from my music. And I write for the Dutch groups like the Schoenberg and Asko Ensemble. These people are great musicians, they are my friends, they have always performed my music. The pieces often fit the size and instrumentation of those orchestras. And so, if my music is only played in those forms, it is ok with me.”

Alas, finally in the last decade, his music began to be performed more and more frequently in the United States. He found new champions at the Los Angeles Philharmonic and New York Philharmonic; he won major awards including the Marie-Josée Kravis Prize for New Music, the Caecilia Prize, and the Grawemeyer Award. He was a role model to younger generations of composers, and a beloved teacher.

I have enormous gratitude for having had the opportunity to know Frederic and Louis, and for being in concert halls and opera houses to hear so many of their greatest pieces. And though the double shock of their passing in such a short time is still hard to fully grasp, I am thankful that their recordings will continue to live as one of the closest expressions of who they were as people, and as creators of some of the most moving, imaginative, and enduring music of our time.

Robert Hurwitz is the Chairman Emeritus of Nonesuch Records.

- Log in to post comments